Masters of Our Own Destiny: Anarchy Beyond Ressentiment

The following is the text of a speech that I delivered at the Second National-Anarchist Movement (N-AM) Conference in Sussex, England, on 24th June 2018

“Too long the earth has been a madhouse.”

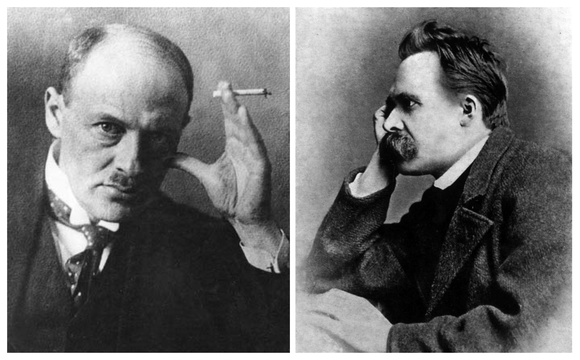

– Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals, II:22

IT is already a well-established fact that National-Anarchists wholeheartedly oppose the State, but what of the accusation frequently levelled at mainstream or left-leaning anarchists with regard to the distinct possibility that such opposition is chiefly motivated by ressentiment? This talk will attempt to examine this controversial issue and explain why National-Anarchists need not suffer from the same dilemma.

According to the dictionary, ‘ressentiment’ is a French term used to denote a particular form of hostility, but should not be confused with the shorter English term, ‘resentment’. Indeed, whilst ‘resentment’ is associated with feelings of spite or anger that are directed at someone or something that may have caused harm to the individual or individuals concerned, ‘ressentiment’ is slightly different in that it relates more specifically to ‘a psychological state resulting from suppressed feelings of envy and hatred which cannot be satisfied.’ Furthermore, ‘ressentiment’ goes much further than ‘resentment’ because it has a reactive function in that a person or group that has actually experienced injustice – perceived or otherwise – decides to respond with some form of action. In other words, ‘ressentiment’ turns ‘resentment’ into attack. By conveniently diverting attention away from the source of their frustration, however, and attempting to belittle their enemies through political or religious morality, victimologists create a scapegoat in order to insulate themselves from culpability.

The word ‘ressentiment’ was first used by the Danish philosopher and theologian, Søren Kierkegaard, who warned against the deceptive and vindictive character of the levelling process. As we shall see, it was later borrowed by his more radical German counterpart, Friedrich Nietzsche. Elsewhere, it was then taken up by the philosophical anthropologist, Max Scheler, who described it as “a special form of human hate” and associated it with the heightening bourgeois morality of Western Europe. In his 1913 study of Ressentiment, published under that very title, Scheler explained that it

is a self-poisoning of the mind which has quite definite causes and consequences. It is a lasting mental attitude, caused by the systematic repression of certain emotions and affects which, as such are normal components of human nature. Their repression leads to the constant tendency to indulge in certain kinds of value delusions and corresponding value judgments. The emotions and affects primarily concerned are revenge, hatred, malice, envy, the impulse to detract, and spite.

Scheler also spoke of a pathological ressentiment, which is

chiefly confined to those who serve and are dominated at the moment, who fruitlessly resent the sting of authority. When it occurs elsewhere, it is either due to psychological contagion—and the spiritual venom of ressentiment is extremely contagious – or to the violent suppression of an impulse which subsequently revolts by “embittering” and “poisoning” the personality.

In psychological terms, we may describe this phenomenon – characterised, perhaps, by the foaming puritans of the authoritarian left and the increasingly silenced reactionaries of the marginalised right – as a classic case of Jungian projection and one which, undoubtedly, leads to an outpouring of negative psychic feelings and, ultimately, repression and denial.

According to Dr. Rüdiger Bittner, based at the University of Bielefeld, the word ‘ressentiment’

is a psychic mechanism. To put it more agreeably perhaps, it is a pattern in people’s reactions to certain experiences. As such a mechanism or pattern, ressentiment explains the slave revolt in morality and thereby, indirectly, our current madness. The slaves, introducing the slave morality under which we are labouring still, were driven by the mechanism, or were reacting in accordance with the pattern, of ressentiment.

The relationship between ressentiment and mainstream or left-leaning anarchism has become a real bone of contention over the last century or so, with the more observant critics of Anarchism seeking to demonstrate that a significant degree of anti-statism and anti-capitalism has more to do with out-and-out jealousy than with principled ideological beliefs, the desire to achieve self-determination, or the restoration of basic human dignity. Indeed, whilst the Establishment has an obvious interest in casting Anarchists in a negative light, or as bearded misfits with an endless supply of Molotov cocktails at their disposal, our long-suffering and grossly misrepresented ideals are hardly likely to be rehabilitated by the opportunistic individuals who simply use Anarchist demonstrations to engage in the kind of hatred and violence that stems from their own lack of emotional and psychological control. Much of what passes for ‘anarchism’, therefore, is actually large-scale ressentiment born of envy, inferiority and, in the worst cases, addiction, psychopathy and mental retardation. These emotional and psychological factors are, inevitably, directed against an external opponent – in this case the State and its mercenaries – who are perceived to be at the root cause of one’s problems.

According to Nietzsche, if a man is naturally dynamic and strong-willed, he is unlikely to develop an inferiority complex. Rather than blame the State, regardless whether it is directly responsible for his actual plight, the superior individual will always try to resolve or overcome this obstacle himself. Indeed, as Robert C. Solomon from the University of Texas explains, and please bear in mind that he uses the term ‘resentment’ and not ‘ressentiment’, Nietzsche

insists that the difference between the weak and the strong is not the occurrence of resentment but its disposition and vicissitudes. A strong character may experience resentment but immediately discharges it in action; it does not “poison” him. But it then becomes clear that objective strength or success cannot be the issue; the poison of resentment works only on those who have frustrated ambitions or desires, whose self-esteem depends on their social status and other measures of personal worth and accomplishment. Thus it is easy to see the wisdom of the Zen master or the Talmudic scholar, who are never poisoned by resentment because they never allow themselves those desires and expectations which can be frustrated and lead to resentment. One always finds great strength and acceptance (not just resignation) among the most abused and downtrodden members of society.

Professor Solomon presents a very good case, although, as we shall discover, Nietzsche’s attitude towards the Jewish religion means that he would not have agreed with the assertion that a Talmudic scholar could be left unaffected by the trappings of ressentiment. Interestingly, even Existentialist philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir believed that seeking to blame one’s predicament on others is a sign of “bad faith” – a philosophical term relating to self-deception – and, as such, that it leads to an inability to realise the conscious self and thus engage in forms of what they described as “authenticated” struggle.

None of this is designed to suggest, of course, that both the State and Capital are not unjust or that people should not fight back against the System whenever and wherever they have a need to defend themselves and their communities, but the fact that a large number of so-called ‘anarchists’ – many of whom are alcoholics and drug addicts – are more interested in seeking confrontation with the police as opposed to working in their own communities or trying to become more self-sufficient and thus improve their own lives, tells us that a substantial percentage of individuals are actively seeking confrontation for non-political reasons.

In his 1887 Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche employs the term ‘ressentiment’ in direct relation to Judeao-Christianity. Nietzsche believed that individuals with an inferiority complex always seek to contain those who are naturally superior by constructing artificial paradigms that portray weakness as a moral good and strength as something wrong and immoral. In order to fully understand Nietzsche’s critique of ressentiment, it is necessary to examine his thoughts on both slave morality and master morality. Prior to the arrival of morality itself, Nietzsche argues, the term ‘good’ was used to refer to those considered to be more noble than their fellows and the term ‘bad’ applied to those who occupied a lower caste status or who were considered to be plebian. This distinction between the high-born and the low-born, on the other hand – which, setting aside modern notions of class, was thought to be determined by nature – was thrown into disarray by the arrival of Judaism:

It was the Jews who, rejecting the aristocratic value equation (good = noble = powerful = beautiful = happy = blessed) ventured with awe-inspiring consistency, to bring about a reversal and held it in the teeth of their unfathomable hatred (the hatred of the powerless), saying, ‘Only those who suffer are good, only the poor, the powerless, the lowly are good; the suffering, the deprived, the sick, the ugly, are the only pious people, the only ones, salvation is for them alone, whereas you rich, the noble, the powerful, you are eternally wicked, cruel, lustful, insatiate, godless, you will also be eternally wretched, cursed and damned!’

This inversion of ancient values led to a slave revolt based on hatred and revenge. Not simply by way of Judaism and Christianity, mark you, but also through pseudo-altruistic movements in the political sphere such as communism, mainstream or left-leaning anarchism and liberal-democracy. Since the 1789 French Revolution, during which a jealous bourgeoisie overthrew its hated enemies in the aristocracy, we have been told to interpret these negative and destructive traits as forms of liberty, equality and fraternity. In order to sustain itself, however, slave morality has to blame its woes on an external threat of some kind. For Anarchists, of course, that threat is the modern nation-state. Make no mistake, the State is a very dangerous and oppressive entity at the best of times, but we need to move away from what is clearly a two-sided dichotomy between Anarchist ressentiment and the State itself.

According to the famous Russian revolutionary, Mikhail Bakunin, who is quoted in the 1984 edition of Political Authority – Scientific Anarchism, it is essential to make a distinction between the “artificial authority” of the State and its man-made laws, on the one hand, and natural authority, on the other. In the words of Saul Newman, Research Associate in Politics at the University of Western Australia, power or artificial authority

is external to the human subject. The human subject is oppressed by this power, but remains uncontaminated by it because human subjectivity is a creation of a natural, as opposed to a political, system. Thus anarchism is based on a clear, Manichean division between artificial and natural authority, between power and subjectivity, between State and society.

The dualism that exists between these two diametrically opposed positions, therefore, is a counter-productive and self-perpetuating process. Unfortunately, Anarchists of this kind define themselves through their opposition to the State, and vice versa. Returning to Newman:

This dialectic of Man and State suggests that the identity of the subject is characterized as essential ‘rational’ and ‘moral’ only insofar as the unfolding of these innate faculties and qualities is prevented by the State. Paradoxically the State, which is seen by anarchists as an obstacle to the full identity of man, is, at the same time, essential to the formation of this incomplete identity. Without this stultifying oppression, the anarchist subject would be unable to see itself as ‘moral’ and ‘rational’. His identity is thus complete in its incompleteness.

This negative approach towards the State is exactly the same as that taken by the slave who considers himself ‘good’ in response to the ‘bad’ character of the master through whom he is seeking to disguise or mask his own inadequacies.

As the famous German novelist and philosopher, Hermann Hesse, notes in one of his short stories:

Our mind is capable of passing beyond the dividing line we have drawn for it. Beyond the pairs of opposites of which the world consists, other, new insights begin.

If anything can make you think outside the box, National-Anarchism can. The State likes nothing more than an opportunity to crack a few Anarchist skulls, just as many Anarchists undoubtedly enjoy confrontation with the authorities. But what purpose does this really serve and what could Anarchists be doing instead? One strategy that is clearly incapable of solving this problem is rapprochement or, in other words, an unthinkable, illogical and unworkable compromise between Anarchists and the ruling class. The solution to the dichotomy between artificial authority and ressentiment, both of which are the result of an inability to come to terms with power and the fact that it ordinarily results in domination, is not to dispense with power altogether but to seek to encourage a will-to-power in the individual. Instead of blaming others for their misfortunes, therefore, the more naturally superior individuals must learn to reject the political, social and economic constraints imposed upon them from without.

This can be achieved by making a determined effort to detach oneself from contemporary society. Not to concern oneself unnecessarily with the effects of State repression or the nihilistic ressentiment that it inspires among mainstream or left-leaning anarchists, but to actually turn one’s back on the State entirely. This may be difficult if one is facing repression on a daily basis, of course, and some communities will be affected far more than others, but unless National-Anarchists make serious efforts to move away from these corrosive areas and establish new communities elsewhere, we will be caught up in the endless Dionysian-Apollonian formula that merely postpones and prolongs the lingering death of Western civilisation. We must defend ourselves and our families, naturally, but very little can be achieved by travelling to a large city centre, wrecking a few buildings, setting fire to a few cars and throwing a few rocks at the police. In fact you may as well ask Mr. Bean to go ten rounds with Mike Tyson.

Nothing but complete and utter detachment – political, economic, emotional and spiritual – can lead to the discovery of our more authentic selves and the fulfilment of what Nietzsche describes as the “inner law”. National-Anarchists must not waste time becoming embroiled in a futile battle between the State oligarchs and those who lurk jealousy in the wings, waiting for a chance to impose their own brand of control on those who dominate them presently. Rather than complain about the education system, we must remove our children from schools and teach them ourselves; become creators, not consumers; forget about the self-perpetuating class war and try thinking about natural aristocracy; stop complaining about the poor standard of modern food and grow our own; cease using official currency and establish community bartering and local exchange trading systems; move away from the cities and large towns and pool our resources with others, buying small plots of land, building alternative houses and re-establishing rural crafts; end the reign of the fuel barons by using wind-power, hydro-power and solar-energy; and, finally, eschew anything which ultimately makes us weak and dependant. By rejecting contemporary society and looking for alternatives, we are also countering the despairing trends of apoliteia and escapism. As Newman explains,

active power is the individual’s instinctive discharge of his forces and capacities which produces in him an enhanced sensation of power, while reactive power, as we have seen, needs an external object to act on and define itself in opposition to.

This, it must be said, is action of the most pure and noble kind.

Nietzsche believed that Apollonian sterility, or systemic decrepitude, should be swept aside like dead wood or put out of its misery like a wounded animal, but the State is still far too strong at this moment in time and a more sensible way in which to impede its ability to function effectively and thus hasten the eventual decline is to weaken it with our own sanctions, boycotts and abstentions. This, after all, is precisely how the global establishment weakens its enemies and therefore we, too, must change our methods of buying and selling to ensure that we do as little as possible to participate in the System or to assist the continuing prosperity of exploitative Capital. One thinks of those living on the periphery of the old Roman Empire, who gradually managed to change their lives in accordance with its decline, but without having to join Alaric and his Goths in the delivery of the final blow. This, after all, even without direct confrontation, is still a fulfilment of the famous Nietzschean maxim,

what is falling, we should still push.

Western civilisation is now creaking along like an old man; any youth and vitality that still remains comes in hues of imported black, brown and yellow. Western dominance is now a waning star, but this is what happens with all civilisations. Some will argue that a rosebush has to be pruned, but this should not mean that the essence of the plant itself must die. This will be true in some cases, but in general it will be impossible to retain anything of civilisation and this means divorcing ourselves from the Manichean dichotomy between the State and reactive anarchism and planting new seeds elsewhere.

This politics of detachment represents a psycho-social transformation and is the only way that anarchists can overcome the fallacy of ressentiment and show the kind of courage and temperament that we need to build an alternative, National-Anarchist future. This is a complete transvaluation of all values, a willing-into-existence that will forever transform our lives and the lives of those we love and cherish. In the words of the great philosopher-poet, John Cowper Powys:

Force those objects round you, however alien, to yield to your defiant resolve to assert yourself through them and against them. Get hold of the moment by the throat. Do not submit to the weakness of waiting for a change. Create a change by calling up the spiritual force from the depths of your being.

In the meantime, without understanding the true value of personal sacrifice, not to mention overcoming their own narcissistic tendencies, those who claim to have an interest in political affairs will remain completely ineffectual and thus have no significant impact whatsoever. In other words, regardless whether you happen to be a vengeful feminist who conceals her misandrist tendencies beneath a pink hat, a class warrior secretly motivated by feelings of jealousy, or even a social misfit who considers himself superior to others on account of having lighter skin: none of you will help to create a better society until you learn to put your emotions to one side and focus on the issue that really matters. Not your feelings, not your own bitterness and ressentiment, nor your irrational hatred of others, but the financial machine that actually controls every aspect of our lives.

So, if you are going to express a political opinion, for goodness sake grow up and do it for the right reasons. Failing that, please consult a psychiatrist.