West Indian Musical Culture and the Crisis of Black Identity

The Jamaican writer, Desmond Richards, interviews Troy Southgate

Q. Please tell our readers about your background.

TS: I SPENT my childhood in South London, England. In many ways, living in that area during the late-1960s and 1970s, as I did, was like growing up in Jamaica. I lived with my parents in Crystal Palace, famous for the huge Victorian building which had once housed the extensive treasures of the British Empire prior to collapsing in a smoking heap of ignominious ashes in 1936. In many ways, therefore, I was raised amid the forgotten ruins of British imperialism. My school was around 30% Caribbean and around us the areas of Brixton, Sydenham, Catford and Lewisham were full of the Jamaican, Trinidadian and Barbadian immigrants which had arrived in London during the late-1950s. The Blacks that I went to school with, therefore, were the very first offspring of those new arrivals and their voices sang with the characteristic melody of that highly-distinct West Indian patois.

Q. What do you remember most about that atmosphere?

TS: Some of my earliest memories include labyrinthine alleyways and pigeon-infested railway bridges, alongside which West Indian traders sold exotic fruit and vegetables or played Calypso, Soca and Reggae music through huge sound systems. And it was this infectious music which acted as a soundtrack to my entire childhood. First capturing my heart and then, over time, piquing my interest until I had reached a much broader appreciation of folk-culture.

Q. When did you start becoming interested in Afro-Caribbean music?

TS: As Punk reared its ugly head in 1977 and I was yet to embark upon the rebelliousness of my teenage years, my own experiences of music had been limited to the Rod Stewart, Abba, Elvis Presley and Carl Orff albums that my parents enjoyed. A year later, whilst attempting to tune in to a football programme, I stumbled across Radio One and the John Peel Show. One act that really stood out for me that night was Kilburn and the High Roads, the band that Ian Dury had formed before The Blockheads had even been a mere twinkle in his mischievous eye. The discovery was crucial, in many ways, and the John Peel Show had opened up a Pandora’s Box of musical delights. It is a well known fact that Madness, the London-based Ska band, were tremendously influenced by Ian Dury and when their first album (One Step Beyond) appeared in 1979 I had already heard the tracks in session on the radio.

Q. What were these new Ska bands like?

TS: Ska music, despite being performed by English or semi-English groups such as Madness, The Specials (Coventry), Bad Manners (London), The Selecter (Coventry), The Beat (Birmingham) and The Bodysnatchers (London), had deep roots that went right back to 1960s Jamaica. As your readers will know, West Indian musicians had picked up American radio broadcasts and then adapted both 1950s Jazz and Rhythm & Blues to form their own distinct sound. The term ‘ska’ refers to the sound made by the strum of the guitar which gives the music its infectious beat. The first big Ska band to arrive on the scene, in 1963, was The Skatalites, with some of the leading performers of the day being Don Drummond (trombone), Baba Brooks (trumpet), Rico Rodiguez (trombone), Tommy McCook (saxophone), Ernest Ranglin (guitar), Lester Sterling (saxophone) and Roland Alphonso (trombone). After discovering Ian Dury and Madness, I went on to buy all of the records that were associated with the Two Tone Records label between 1979 and 1981, some of the most notable releases being Gangsters (The Special AKA), The Prince (Madness), On My Radio (The Selecter), Tears of a Clown (The Beat), Too Much Too Young (The Specials), Three Minute Hero (The Selecter), Missing Words (The Selecter), Stereotype (The Specials), Do Nothing (The Specials), Ghost Town (The Specials), The Boiler (The Bodysnatchers) and many others. Madness released just the one single on Two Tone before moving over to Stiff Records and becoming one of the most successful and enduring bands in English musical history. The Beat did the same when they moved across to Go-Feet Records and one of their b-sides, in particular, Stand Down Margaret, is directly responsible for my own politicisation.

Q. So how did you hear about the earlier stuff from Jamaica?

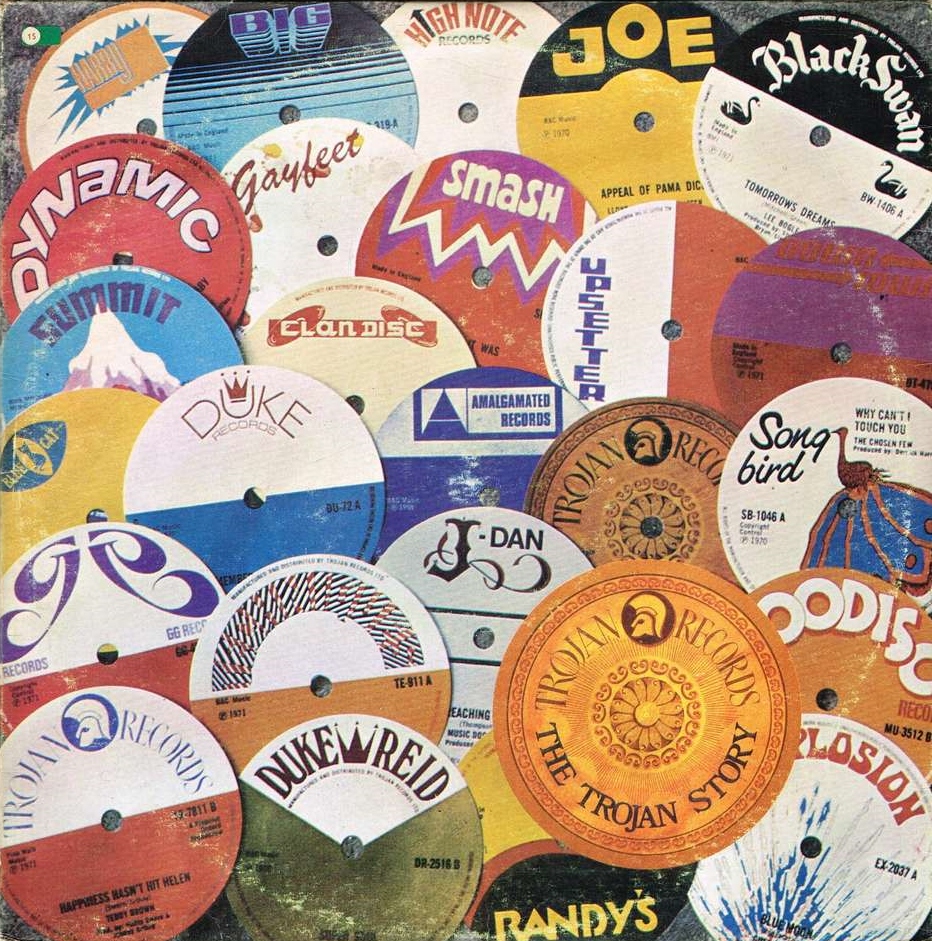

TS: During the long, summer holidays, I often went to stay with my aunt in Catford, and naturally took my expanding vinyl collection along with me. On one occasion she heard me playing One Step Beyond by Madness and told me that it reminded her of the Ska music that she had listened to back in the 1960s. That was the moment when another musical door was prised open and, before long, she had passed all of her old records on to me and I began tracking down the original Ska and Reggae releases that had been put out on the Studio One, Trojan, Pama, Blue Beat and Coxsone Dodd labels by Jamaican-based artists such as Prince Buster (forever immortalised by Madness in songs like The Prince, One Step Beyond and Madness), Laurel Aitken, Jimmy Cliff, The Pioneers, Dave & Ansell Collins, The Maytals, Derrick Morgan and The Upsetters. There was also the English artist, Judge Dread, who had several of his saucy releases banned from the charts. One leading crossover Reggae artist, Johnny Nash, lived in our block of flats near Brixton and another, Desmond Dekker, lived a few doors away from my grandmother’s home in nearby Forest Hill. Although this music had always been there during my formative years, I hadn’t really made the connection until my aunt highlighted the lineage that existed between the new wave of British Ska and that of its West Indian forebears more than a decade earlier.

Q. How did the music affect your lifestyle?

TS: Back in 1969, Reggae music had been taken up by the emerging skinhead movement and some of the West Indian groups began mentioning the skinhead connection on their albums. These included Symarip’s famous Skinhead Moonstomp release, which was covered almost a decade later by The Specials on their chart-topping Too Much Too Young EP. In 1979, when the second wave of Ska really took off, I became a skinhead myself and remained so until the 1990s. Skinheads today are usually associated with the White Power movement, but their musical roots are inextricably bound up with the Ska and Reggae music that began arriving at the London docks in the 1960s. An obsession with clothes soon developed and by day I could be seen wearing a colourful array of Ben Sherman shirts, stapress trousers, harrington jackets and huge bovver boots. By night, if we were going out, I wore smart crombie coats with velvet collars and paisley cravats, all finished off with polished brogues or tasselled loafers. I had a penchant for suits, too, and wore a variety of patterns including two-tone tonic, dog tooth and Prince of Wales check. Many of these clothes were found in old charity shops, where the previous generation had disposed of them and thus enabled us to give them a new lease of life. Our little gang was made up of some of the smartest skinheads of all and we certainly put the ‘plastic’ T-shirt and jeans brigade to shame when we turned up at the skinhead pubs and clubs.

Q. But the Ska period in the UK was fairly short-lived, right?

TS: Yes. Once the second wave began to fade in 1981, just as Ghost Town (The Specials) was becoming the soundtrack for the summer riots affecting many of our English cities, I found myself becoming rather alarmed that British Ska was coming to an end. My friends were listening to chart music, growing their hair and becoming casuals (i.e. ‘norms’), whilst I attempted to remain true to my skinhead roots and refused to kowtow to the changing mores of the fashion industry. I tried to console myself with some of the Oi! Music that was also beginning to appear among skinheads, although it was quite different to what I had been used to. Nevertheless, bands like The Last Resort and The 4-Skins were a decent substitute and a way for the skinhead movement to stay alive through the dark days of the 1980s.

Q. You mentioned that you had a taste for the old Ska sounds of the 1960s, but what about some of the more recent music that was coming out of Jamaica around that time?

TS: My love for Jamaican music went far beyond the Ska genres of the 1960s, late-1970s and early-1980s and I became immersed in the Reggae music ordinarily associated with Rastafarianism. I found it fascinating that this religion – born in the 1930s and considered to be little more than a fashion as far as most people are concerned – not only involved an identification with the Twelve Tribes of Israel and the worship of the late Emperor Haile Selassie I (1892-1975) of Ethiopia as the Messiah, but that its dread-locked adherents also had strict dietary requirements (I-tal) and rejected contemporary Western society (‘Babylon’) in favour of their own spiritual ‘Zion’ (Africa). I’m obviously preaching to the converted here, Desmond!

Q. That’s okay, man! What kind of records were you buying back then?

TS: One of the first Reggae albums that I bought with a strictly Rastafarian theme was Aswad’s Back to Africa LP, released in 1976 on the Island Records label. The music had a huge impact on me, not least because I identified with some of the themes about slavery and inner-city squalor. The title track, meanwhile, had the biggest influence of all and, apart from the outstanding musical ability of Aswad themselves, the lyrics conjure up a vision that is both noble and spiritual at the same time:

Open your eyes

And you will see

A far off land

For you and me

Africa is her name

A place

Where we’ll be free

Once again

Q. Why did those lyrics affect you so much?

TS: It is difficult to remain unmoved by such sentiments, particularly when you consider the acts of cruelty inflicted on Blacks throughout the last few centuries. That is not to say that Black people should continue to portray themselves as victims or that White people should perceive them in that way, of course, because people of all nations have suffered at the hands of capitalism and exploitation and in terms of presenting a viable solution for those Blacks who feel dislocated here in Europe, one cannot fault the sentiments:

Got to leave

These critical states

We got to get out

Before it’s too late

Free ourselves

From all persecutions

Got to get free

From the wicked Babylon

Q. Did you notice these themes running all the way through Aswad’s early material?

TS: Without a doubt. Another good example of the group’s awareness that Afro-Caribbeans were out of place in English society was the song African Children. Here are some of the lyrics:

Many African children,

Living in a concrete situation

African children

Living in a concrete situation

African children

I wonder do they know where you’re coming from

African children

Down there yes in a concrete situation

African children

I wonder do they know where you’re coming from

The whole of the nation

Living in these tenements,

Crying and applying to their council

For assistance every day

Now that their tribulation so sad

Now that their environment so bad

High-rise concrete

No back yard

For their children to play

African children

I wonder do they know where you’re coming from,

African children

In a concrete situation

African children

Wonder do they know where you’re coming from

All of the nation are living in these tenements

Pre-cast stonewall concrete cubicles

Their rent increases each and every other day

Structural repairs are assessed yet not done

Lift out of action on the twenty-seventh floor

And when they work they smell

Q. Where did you pick up this material?

TS: Aswad’s material was always fairly easy to track down, but I managed to get a lot of rare imports from record shops in and around Brixton. I also visited Dub Vendor in nearby Clapham Junction and even some specialist shops in the home counties that have since bitten the dust. I found it very interesting how the various forms of Reggae – which were often very diverse – were each influenced by the popular bassline that happened to be doing the rounds at the time. These included things like the ‘murderer’ and ‘bicycle move’ basslines, which could easily be detected in anything from Dub and Dance Hall to Roots and Lover’s Rock and which lasted for about a month until a new one came along to replace it. I used to collect all of the records on the Greensleeves label, too, which was a Shepherds Bush outlet that sold both albums and 12” singles that included the vocal song on one side and a Dub track (or ‘version’) on the other. These things were always hot off the press from Jamaica and I was pretty clued-up for a teenage White boy and this surprised a lot of the people who worked at those places. I obtained most of my information from the Reggae Rockers radio show, hosted by DJ Tony Williams on Sunday afternoons, or from the pages of the Black Echoes music paper. In this respect, I suppose that I was a bit of a cultural oddity. The fact that I had grown up in South London had an enormous amount to do with this, of course.

Q. Who were your favourite artists?

TS: Aswad, at least in the early days, were always my favourite band, but in the 1980s I was listening to Yellowman, Dennis Brown, Eek-A-Mouse, Smiley Culture, Black Uhuru, Sly & Robbie, Sugar Minott, Winston Reedy, Jah Shaka, Lee Perry, Dennis Bovell, Mad Professor, Scientist and hundreds of others. I was often the only White face at some of the concerts in those days, too, especially when it was a tiny club featuring a local sound system.

Q. But throughout this period you still understood that young Afro-Caribbeans felt very out of touch with British society?

TS: Certainly. I remember listening to Linton Kwesi Johnson’s Doun De Road and its references to the National Front being ‘on the rampage.’ That is an exaggeration, in my opinion, at least in retrospect, but as a young teenager with both an understanding and an awareness of Black history I did feel that there was a sense of injustice about their predicament. Ironically, as you know, I ended up joining the National Front myself several years later, although it had changed a great deal by that time and I was drawn to the organisation as a result of its economic policies and strong working class identity.

Q. That’s quite a big leap for someone who was into Black music in such a big way.

TS: Sure. I knew about the National Front’s reputation, but I also had one or two friends who had joined the organisation and felt satisfied that a lot of the media hype about the group had been vastly exaggerated. I voted for the Labour Party when I was eighteen and considered myself a socialist, but after becoming disillusioned with Labour’s ability to deal with Margaret Thatcher I began examining the National Front’s literature about workers’ co-operatives, distributism and decentralisation. I only accepted the Race issue later on, but I never met anyone who had engaged in racial attacks against Black people or who fitted the stereotypical media image. The National Front was in the process of expelling its Nazi elements at that time, anyway.

Q. So was the NF still calling for immigrants to be sent home?

TS: When I first joined the organisation, yes. I found that fairly harsh, to be perfectly honest, and wondered how on earth it could ever be achieved without great suffering and hardship. But that Aswad song was always there at the back of my mind, telling me that things might be different for all races if people lived in their lands of ethnic origin. I supported humane repatriation in the late-1980s, but I eventually realised that it was completely unrealistic and that another solution had to be found.

Q. I myself went to Jamaica, where my parents had come from, you know. So I’m one of the few people who believed that repatriation was the right thing to do and went through with it.

TS: Exactly and I admire you for that. But I think that things have gone too far in certain European countries and that racial separatism will only happen on a regional basis. As an Anarchist, of course, I don’t believe in dividing up entire countries as part of one enormous plan, but I think we will see a general trend for people to live among their own kind. That won’t happen as long as we have the nation-state breathing down our necks, but that’s really the only thing that is holding this semi-fractured ‘nation’ together and the sooner we get rid of it the better for all concerned.

Q. We have similar problems in Jamaica. The island is not the paradise that people think it is and there are still massive differences between rich and poor. Did you continue listening to Black music into the 1990s and then up to the present day?

TS: I still listen to the old material, obviously, but in the 1980s there was a significant sea-change and I began to notice that Black people began to behave a lot differently to the way they had in the past.

Q. How do you mean?

TS: In the middle of that decade I noticed the rise of Hip Hop and Breakdancing, which began to gain a serious foothold among English teenagers. Initially, I regarded it as just another trend, but over time the entire attitude of Black youth began to change and the lyrical content of the songs became more negative and fratricidal. I hated it, to be perfectly honest, and was still listening to the kind of music that some of their fathers and grandfathers had made, but this new wave of Black music from America was extremely different to the West Indian style and Black people began to accept a more globalised and cosmopolitan form of culture.

Q. But the music still gave the youth an identity, right?

TS: It gave them the wrong kind of identity. It was no longer Afro-centric and the lyrics were less concerned with their African roots than with gun crime, drugs and an increasingly negative portrayal of women. This became far worse with the advent of Rap music, of course.

Q. So, the music that came after Reggae was basically American. Is that what you’re saying?

TS: Yes. Black identity became completely subsumed within a morass of Americanisation and it had a negative effect on all people, too, whether they were Black or White. Back in London, in the 1970s, Black families had a very strong identity, not least as a result of the fact that West Indians were outsiders and this helped to strengthen their communities. The pernicious anti-culture that was emanating from America, on the other hand, led to rapid fragmentation and Anglo-Jamaican men, in particular, are known for leaving a trail of single mothers in their wake.

Q. It’s true. This has even been discussed in the Jamaican media.

TS: Black women have also expressed concern at the number of Black men who are attracted to White women and the number of half-caste offspring in the British Isles is quite staggering.

Q. So you feel that the new wave of Black music had a role to play in all this?

TS: To a large extent, although mass immigration inevitably results in racial miscegenation and cultural extinction. With all due respect, if Black people had continued to remain true to their roots they would not be experiencing the kind of identity crisis that they face today. The same is true of White teenagers, too, of course. But what is significant, I think, is that both Black and White youth are following the negative and damaging trends that have arrived from America.

Q. I have to agree with you. But what do you think can be done about this?

TS: I think it is up to Black people to solve their own problems. There does remain a semblance of Black identity in some parts of the British Isles, not least among those who go to all that effort to organise the Notting Hill Carnival every year. However, you don’t see very much in the way of community on the dilapidated council estates and that has to change. Positive steps have been taken to counteract the spread of gun crime, for example, but you do not see many Black people involving themselves in community life to any great extent. A few years ago I attended a boot fair, for example, which was held in a West Indian part of London, and every single person behind the stalls happened to be White. Now, what does that say about Black people getting involved in the community and taking the initiative for themselves? Some are active within their churches and mosques, certainly, but the West Indian identity has become completely submerged. I think the tide can be reversed, however, especially if the people who still follow Reggae music can promote some of the Afro-centric messages that lie behind this material. West Indian record fairs, concerts and social events would be a step in the right direction. Promoting this more positive message in direct opposition to the continuing encroachment of Americanisation would be a good way of fighting back. Especially when you consider that an entirely new generation of Black Africans has now descended on the existing West Indian communities. They could be useful allies in this process. And it’s not like West Indians themselves have not achieved all this in the past, either.

Q. This has been very interesting. Thanks for your time, Troy.

TS: Thanks, Desmond. It has been a great pleasure.

[Desmond Richards is a pseudonym]