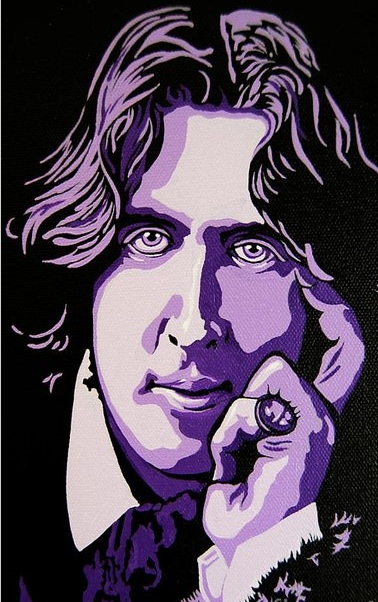

ANARCHY IN ALL BUT NAME: A FRESH LOOK AT OSCAR WILDE’S ‘THE SOUL OF MAN UNDER SOCIALISM’

WRITTEN in 1891, The Soul of Man Under Socialism was the first political essay to appear in the immediate aftermath of Oscar Wilde’s (1854-1900) dramatic conversion to Anarchism. Apart from his widely celebrated philosophical novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), this leading Irish playwright with a wonderfully satirical imagination and remarkable turn of phrase is possibly best remembered for his homosexuality (“the love that dare not speak its name”) at a time when it was still punishable by law.

Indeed, on April 6th, 1895, Wilde was arrested for sodomy and gross indecency under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 and forced to stand trial. On May 25th, 1895 he was convicted and given two years’ hard labour, whilst the Judge made a point of saying that if the judicial means were available he would have increased the sentence further. Wilde was incarcerated until May 18th, 1897, by which time he had served this low period of his life in four separate prisons: Newgate, Pentonville, Wandsworth and Reading. On his release, Wilde’s miserable experiences led him to compose the moving poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1897), with one verse later appearing as the epitaph on his tomb:

And alien tears will fill for him,

Pity’s long-broken urn,

For his mourners will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.

The Soul of Man Under Socialism is an exercise in the kind of principled libertarian socialism that went on to inspire the likes of A.R. Orage (1873-1934), Herbert Read (1893-1968), George Orwell (1903-1950) and many others. This is why we must not associate Wildean ‘Socialism’ with the incalculable horrors of the Russian and Chinese variants that appeared during the following century. Socialism, for Wilde, has nothing whatsoever in common with the perversely repressive belief-system of the modern Left. In addition, the fact that he had railed so strongly against the British state’s attempts to tell him what to do with his own body was a clear indication of his committed anti-authoritarianism.

Wilde begins his work by outlining the general principle of true Socialist values and its emancipatory spirit:

The chief advantage that would result from the establishment of Socialism is, undoubtedly, the fact that Socialism would relieve us from that sordid necessity of living for others which, in the present condition of things, presses so hardly upon almost everybody. In fact, scarcely anyone at all escapes.

Wilde is referring to the claustrophobic nature of modern civilisation and his words immediately recall the natural ‘outsider’ that was mentioned so fleetingly during the course of The Ballad of Reading Gaol. Men and women of this calibre, he argues, must not be shackled by the shallow principles of mass society:

Now and then, in the course of the century, a great man of science, like Darwin; a great poet, like Keats; a fine critical spirit, like M. Renan; a supreme artist, like Flaubert, has been able to isolate himself, to keep himself out of reach of the clamorous claims of others, to stand ‘under the shelter of the wall,’ as Plato puts it, and so to realise the perfection of what was in him, to his own incomparable gain, and to the incomparable and lasting gain of the whole world. These, however, are exceptions.

He goes on to describe the individuals who, moved by a nagging conscience, actively try to remedy the incalculable ills of contemporary society:

The majority of people spoil their lives by an unhealthy and exaggerated altruism – are forced, indeed, so to spoil them. They find themselves surrounded by hideous poverty, by hideous ugliness, by hideous starvation. It is inevitable that they should be strongly moved by all this. The emotions of man are stirred more quickly than man’s intelligence; and, as I pointed out some time ago in an article on the function of criticism, it is much more easy to have sympathy with suffering than it is to have sympathy with thought. Accordingly, with admirable, though misdirected intentions, they very seriously and very sentimentally set themselves to the task of remedying the evils that they see. But their remedies do not cure the disease: they merely prolong it. Indeed, their remedies are part of the disease.

Wilde argues that the philanthropist approach is to keep the poor alive by any means necessary, and to provide them with a basic sustenance in the hope that such people will be distracted from the degradation that surrounds them. It is, as he explains, a wholly fruitless exercise:

But this is not a solution: it is an aggravation of the difficulty. The proper aim is to try and reconstruct society on such a basis that poverty will be impossible. And the altruistic virtues have really prevented the carrying out of this aim. Just as the worst slave-owners were those who were kind to their slaves, and so prevented the horror of the system being realised by those who suffered from it, and understood by those who contemplated it, so, in the present state of things in England, the people who do most harm are the people who try to do most good; and at last we have had the spectacle of men who have really studied the problem and know the life – educated men who live in the East End – coming forward and imploring the community to restrain its altruistic impulses of charity, benevolence, and the like. They do so on the ground that such charity degrades and demoralises. They are perfectly right. Charity creates a multitude of sins.

Whilst it may seem alarming for a self-professed Socialist to question the attitude of the average humanitarian, he clearly has a point. Either prolonging or perpetuating human misery through temporary alleviation does not solve it in the long term.

The alternative, for Wilde, would lead to nobody

living in fetid dens and fetid rags, and bringing up unhealthy, hunger-pinched children in the midst of impossible and absolutely repulsive surroundings. The security of society will not depend, as it does now, on the state of the weather. If a frost comes we shall not have a hundred thousand men out of work, tramping about the streets in a state of disgusting misery, or whining to their neighbours for alms, or crowding round the doors of loathsome shelters to try and secure a hunch of bread and a night’s unclean lodging. Each member of the society will share in the general prosperity and happiness of the society, and if a frost comes no one will practically be anything the worse.

Although it sounds as though the author is advocating a modified version of the mass society, with everyone pulling together in typically collectivist fashion, Wilde also believed that Socialism would lead to ‘Individualism’. Whilst the conversion of private property into public wealth will transform society back into a healthy organism, he contends, it will have an impact at the more fundamental level:

It will, in fact, give Life its proper basis and its proper environment. But for the full development of Life to its highest mode of perfection, something more is needed. What is needed is Individualism. If the Socialism is Authoritarian; if there are Governments armed with economic power as they are now with political power; if, in a word, we are to have Industrial Tyrannies, then the last state of man will be worse than the first. At present, in consequence of the existence of private property, a great many people are enabled to develop a certain very limited amount of Individualism. They are either under no necessity to work for their living, or are enabled to choose the sphere of activity that is really congenial to them, and gives them pleasure. These are the poets, the philosophers, the men of science, the men of culture – in a word, the real men, the men who have realised themselves, and in whom all Humanity gains a partial realisation.

It could be argued that Wilde is suggesting that people such as himself, the makers and shapers of this world, should receive some kind of privileged status on account of their superior intellectual faculties. However, he is simply differentiating between those who have the time to engage in such pursuits and the kind of inhuman rabble that is created by industrial capitalism:

Upon the other hand, there are a great many people who, having no private property of their own, and being always on the brink of sheer starvation, are compelled to do the work of beasts of burden, to do work that is quite uncongenial to them, and to which they are forced by the peremptory, unreasonable, degrading Tyranny of want. These are the poor, and amongst them there is no grace of manner, or charm of speech, or civilisation, or culture, or refinement in pleasures, or joy of life. From their collective force Humanity gains much in material prosperity. But it is only the material result that it gains, and the man who is poor is in himself absolutely of no importance. He is merely the infinitesimal atom of a force that, so far from regarding him, crushes him: indeed, prefers him crushed, as in that case he is far more obedient.

The rank of makers and shapers to which Wilde alludes, therefore, may have thrived within the capitalist system in a way that the poor and downtrodden of Victorian England were never able to do, but at the same time this should never preclude the lower classes from raising themselves to a higher level under Socialism. By removing property from private hands, Wilde hoped that the natural virtues of the poor – hidden, as a light beneath the proverbial bushel – would come to flourish. This is what Wilde means by ‘Individualism,’ the potential for an individual to express their true nature without the capitalist slave-master breathing down his neck. For him, it was a matter of rethinking the dynamics of property:

The possession of private property is very often extremely demoralising, and that is, of course, one of the reasons why Socialism wants to get rid of the institution. In fact, property is really a nuisance. Some years ago people went about the country saying that property has duties. They said it so often and so tediously that, at last, the Church has begun to say it. One hears it now from every pulpit. It is perfectly true. Property not merely has duties, but has so many duties that its possession to any large extent is a bore. It involves endless claims upon one, endless attention to business, endless bother. If property had simply pleasures, we could stand it; but its duties make it unbearable. In the interest of the rich we must get rid of it.

Wilde, almost certainly, had been inspired by the Mutualist ideas of the leading French Anarchist, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865), whose famous 1840 work Qu’est-ce que la propriété? Recherche sur le principe du droit et du gouvernement (What is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government) equated private property with calculated expropriation. In Proudhon’s own words:

If I were asked to answer the following question: What is slavery? and I should answer in one word, It is murder!, my meaning would be understood at once. No extended argument would be required to show that the power to remove a man’s mind, will, and personality, is the power of life and death, and that it makes a man a slave. It is murder. Why, then, to this other question: What is property? may I not likewise answer, It is robbery!, without the certainty of being misunderstood; the second proposition being no other than a transformation of the first?

As we have seen, although The Soul of Man Under Socialism called for an end to large-scale private property – as opposed to small-scale individual ownership – Wilde was opposed to charity in the sense that it not only failed to tackle the deeper problems of industrial capitalism but also prevented the poor from actively pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps. Besides, he insisted, charity was never received in the right spirit:

We are often told that the poor are grateful for charity. Some of them are, no doubt, but the best amongst the poor are never grateful. They are ungrateful, discontented, disobedient, and rebellious. They are quite right to be so. Charity they feel to be a ridiculously inadequate mode of partial restitution, or a sentimental dole, usually accompanied by some impertinent attempt on the part of the sentimentalist to tyrannise over their private lives. Why should they be grateful for the crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table? They should be seated at the board, and are beginning to know it.

On the other hand, unlike the deluded philanthropists of the nineteenth century – not to mention our own – Wilde did not propose that the poor become more thrifty in order to better account for their own needs, because it is simply impossible for people who live in such pitiful circumstances to cultivate a more noble character:

As for being discontented, a man who would not be discontented with such surroundings and such a low mode of life would be a perfect brute. Disobedience, in the eyes of anyone who has read history, is man’s original virtue. It is through disobedience that progress has been made, through disobedience and through rebellion.

Rather than accept charity, says Wilde, the poor must rise up and free themselves from tyranny. It is difficult to imagine, of course, how a man who becomes a brute on account of his circumstances could ever manage to become a principled revolutionary, but Wilde is nonetheless aware that a very special type of person is called for:

Misery and poverty are so absolutely degrading, and exercise such a paralysing effect over the nature of men, that no class is ever really conscious of its own suffering. They have to be told of it by other people, and they often entirely disbelieve them. What is said by great employers of labour against agitators is unquestionably true. Agitators are a set of interfering, meddling people, who come down to some perfectly contented class of the community, and sow the seeds of discontent amongst them. That is the reason why agitators are so absolutely necessary. Without them, in our incomplete state, there would be no advance towards civilisation.

It is unfortunate that certain aspects of Wilde’s own Socialist vision were dependent on the kind of progressivist tendencies advocated by people such as fellow Irishman George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) and English novelist H.G. Wells (1866-1946), but this was wholly keeping with the spirit of the age. He was unable to appreciate the fact that the worst excesses of the modern world were themselves a result of civilisational development and that a more organic solution was required. At the same time, he was perfectly aware that the denizens of the British Left were not promoting real Socialist values and Wilde’s observations offered a prescient warning about the Communist totalitarianism that would appear less than two decades after his death:

It is clear, then, that no Authoritarian Socialism will do. For while under the present system a very large number of people can lead lives of a certain amount of freedom and expression and happiness, under an industrial-barrack system, or a system of economic tyranny, nobody would be able to have any such freedom at all. It is to be regretted that a portion of our community should be practically in slavery, but to propose to solve the problem by enslaving the entire community is childish. Every man must be left quite free to choose his own work. No form of compulsion must be exercised over him. If there is, his work will not be good for him, will not be good in itself, and will not be good for others. And by work I simply mean activity of any kind.

What actually distinguishes Wilde’s political outlook from other so-called ‘Socialists’ is the issue of coercion:

I confess that many of the socialistic views that I have come across seem to me to be tainted with ideas of authority, if not of actual compulsion. Of course, authority and compulsion are out of the question. All association must be quite voluntary. It is only in voluntary associations that man is fine.

At this point, The Soul of Man Under Socialism pins its Anarchist colours firmly to the mast and we recognise the healthy anti-authoritarian traits that one finds in the ground-breaking work of William Godwin (1756-1836), Max Stirner (1806-1856), William Morris (1834-1896), Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921) and many others.

Wilde then turns his attention back to the makers and shapers who have live radically different lives to those of the poor, arguing that whilst it may seem harsh to remove private property from the country’s famous poets and writers – particularly those who took care of their own needs without exploiting others – doing so would effectively help people to attain an even more elevated and refined ‘Individualism’. Wilde’s use of the term is not meant in the way that anarcho-individualists like Stirner were rejecting society and reducing humans to a single unit, but in the sense that an individual could reach true fulfilment. The Swiss psychologist, Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), would later refer to this process as ‘individuation,’ and from the Wildean perspective it meant that the

true perfection of man lies, not in what man has, but in what man is. Private property has crushed true Individualism, and set up an Individualism that is false. It has debarred one part of the community from being individual by starving them. It has debarred the other part of the community from being individual by putting them on the wrong road, and encumbering them.

Furthermore, this disastrous process had been aided and abetted by the judiciary:

English law has always treated offences against a man’s property with far more severity than offences against his person, and property is still the test of complete citizenship.

Removing property, Wilde claimed, would erase the desire to acquire social status through endless accumulation and this – or so he hoped – would turn the heads and hands of the most creative people towards art. But although art has allowed people to express the fullness of their personalities, this has never been achieved in action and Wilde attacks the defects and insecurities of those historical figures who are considered ‘great’ and yet who spent their lives in turmoil. Peace and contentment, he argues, does not come from endless struggle, although he is perhaps slightly utopian in his belief that the implementation of Socialism would ever bring an end to the need for defence. Nevertheless, his dream of a world in which materialism is swept aside remains inspiring:

It will be a marvellous thing – the true personality of man – when we see it. It will grow naturally and simply, flowerlike, or as a tree grows. It will not be at discord. It will never argue or dispute. It will not prove things. It will know everything. And yet it will not busy itself about knowledge. It will have wisdom. Its value will not be measured by material things. It will have nothing. And yet it will have everything, and whatever one takes from it, it will still have, so rich will it be. It will not be always meddling with others, or asking them to be like itself. It will love them because they will be different. And yet while it will not meddle with others, it will help all, as a beautiful thing helps us, by being what it is. The personality of man will be very wonderful. It will be as wonderful as the personality of a child.

Wilde’s vision of a brighter future did not rule out the need for Christianity, either, if people embraced it of their own volition and without coercion. Christ, he suggests, was the harbinger of something that was rather similar to Socialism in both word and deed:

‘Know thyself’ was written over the portal of the antique world. Over the portal of the new world, ‘Be thyself’ shall be written. And the message of Christ to man was simply ‘Be thyself.’ That is the secret of Christ.

Just as Wilde wished to see the abolition of private property, so too did he apply this belief to the institution of marriage and the family at large:

This is part of the programme. Individualism accepts this and makes it fine. It converts the abolition of legal restraint into a form of freedom that will help the full development of personality, and make the love of man and woman more wonderful, more beautiful, and more ennobling. Jesus knew this. He rejected the claims of family life, although they existed in his day and community in a very marked form. ‘Who is my mother? Who are my brothers?’ he said, when he was told that they wished to speak to him. When one of his followers asked leave to go and bury his father, ‘Let the dead bury the dead,’ was his terrible answer. He would allow no claim whatsoever to be made on personality.

It is hard to see how marriage and family life can be removed from Christianity, particularly when one considers that Jesus performed a miracle at the Wedding of Cana and may even have married Mary Magdalen, but Wilde – perhaps as a result of his homosexuality – seemed adamant that it was a necessary part of the Socialist vision.

The section of The Soul of Man Under Socialism that deals with rule of government is absolutely unequivocal and there is little doubt that Wilde had become an Anarchist:

Individualism, then, is what through Socialism we are to attain to. As a natural result the State must give up all idea of government. It must give it up because, as a wise man once said many centuries before Christ, there is such a thing as leaving mankind alone; there is no such thing as governing mankind. All modes of government are failures. Despotism is unjust to everybody, including the despot, who was probably made for better things. Oligarchies are unjust to the many, and ochlocracies are unjust to the few.

So-called democracy, too, also comes in for a welcome degree of criticism:

High hopes were once formed of democracy; but democracy means simply the bludgeoning of the people by the people for the people. It has been found out. I must say that it was high time, for all authority is quite degrading. It degrades those who exercise it, and degrades those over whom it is exercised. When it is violently, grossly, and cruelly used, it produces a good effect, by creating, or at any rate bringing out, the spirit of revolt and Individualism that is to kill it. When it is used with a certain amount of kindness, and accompanied by prizes and rewards, it is dreadfully demoralising. People, in that case, are less conscious of the horrible pressure that is being put on them, and so go through their lives in a sort of coarse comfort, like petted animals, without ever realising that they are probably thinking other people’s thoughts, living by other people’s standards, wearing practically what one may call other people’s second-hand clothes, and never being themselves for a single moment. ‘He who would be free,’ says a fine thinker, ‘must not conform.’ And authority, by bribing people to conform, produces a very gross kind of over-fed barbarism amongst us.

Curiously, Wilde believed that with the abolition of government and democracy, the state could nonetheless be retained:

Now as the State is not to govern, it may be asked what the State is to do. The State is to be a voluntary association that will organise labour, and be the manufacturer and distributor of necessary commodities. The State is to make what is useful. The individual is to make what is beautiful.

Naturally, Wilde’s notion of the ‘state’ is far more similar to Muammar al-Qathafi’s (1942-2011) Jamahiriya, or ‘state of the masses’. Applied in Libya, much to the chagrin of the imperialist Western powers, this rather loose version of a ‘state’ merely existed in order to channel the wishes of the people from street and area committees right through to the regional and national level. Despite Qathafi’s role as figurehead, at no time were Libyans labouring under a government in the way that it is ordinarily understood.

Wilde was unable to see the technological developments that plague us today, believing that machinery would become an aid to Socialist revolution and bring freedom:

I cannot help saying that a great deal of nonsense is being written and talked nowadays about the dignity of manual labour. There is nothing necessarily dignified about manual labour at all, and most of it is absolutely degrading. It is mentally and morally injurious to man to do anything in which he does not find pleasure, and many forms of labour are quite pleasureless activities, and should be regarded as such. To sweep a slushy crossing for eight hours, on a day when the east wind is blowing is a disgusting occupation. To sweep it with mental, moral, or physical dignity seems to me to be impossible. To sweep it with joy would be appalling. Man is made for something better than disturbing dirt. All work of that kind should be done by a machine.

Although Wilde believed that the removal of private property would enable machines to create more leisure, he failed to understand that without people slaving away in capitalist factories there would be no more production. This is perfectly fine in the eyes of the present writer, but Wilde’s version of Socialism imagined that such production would continue:

Were that machine the property of all, every one would benefit by it. It would be an immense advantage to the community. All unintellectual labour, all monotonous, dull labour, all labour that deals with dreadful things, and involves unpleasant conditions, must be done by machinery. Machinery must work for us in coal mines, and do all sanitary services, and be the stoker of steamers, and clean the streets, and run messages on wet days, and do anything that is tedious or distressing. At present machinery competes against man. Under proper conditions machinery will serve man. There is no doubt at all that this is the future of machinery, and just as trees grow while the country gentleman is asleep, so while Humanity will be amusing itself, or enjoying cultivated leisure – which, and not labour, is the aim of man – or making beautiful things, or reading beautiful things, or simply contemplating the world with admiration and delight, machinery will be doing all the necessary and unpleasant work.

Again, it is hard to see how those making and assembling the machines would find the experience fulfilling and surely modern forms of technology would need to undergo an extensive regression or even disappear completely in order for Socialism to thrive?

Returning to the question of art, Wilde explained that production of this kind – something beautiful, rather than born of necessary – would reach a higher level due to the individual creating for himself and not for others. The individual, too, would benefit:

An individual who has to make things for the use of others, and with reference to their wants and their wishes, does not work with interest, and consequently cannot put into his work what is best in him. Upon the other hand, whenever a community or a powerful section of a community, or a government of any kind, attempts to dictate to the artist what he is to do, Art either entirely vanishes, or becomes stereotyped, or degenerates into a low and ignoble form of craft. A work of art is the unique result of a unique temperament. Its beauty comes from the fact that the author is what he is. It has nothing to do with the fact that other people want what they want. Indeed, the moment that an artist takes notice of what other people want, and tries to supply the demand, he ceases to be an artist, and becomes a dull or an amusing craftsman, an honest or a dishonest tradesman. He has no further claim to be considered as an artist. Art is the most intense mode of Individualism that the world has known. I am inclined to say that it is the only real mode of Individualism that the world has known.

Wilde is under no illusions about the public reaction towards art and accepts that vulgar attitudes by those who fail to appreciate its subtleties will always exist. Ironically, this can often swing in the individual’s favour:

On the whole, an artist in England gains something by being attacked. His individuality is intensified. He becomes more completely himself. Of course, the attacks are very gross, very impertinent, and very contemptible. But then no artist expects grace from the vulgar mind, or style from the suburban intellect. Vulgarity and stupidity are two very vivid facts in modern life. One regrets them, naturally. But there they are. They are subjects for study, like everything else. And it is only fair to state, with regard to modern journalists, that they always apologise to one in private for what they have written against one in public.

The Soul of Man Under Socialism then wanders off into a lengthy discussion about the nature of art itself, although many of Wilde’s remarks seem out of place in an essay of this kind and he tends to imagine a Socialist future in which prevailing attitudes to art are retained. In reality, for any effective revolution to take place there would have to be a fundamental change in human consciousness. As a result, attitudes towards art – or anything else, for that matter – will most likely have evolved or devolved. In this sense, at least, Wilde seemed trapped within the mental straight-jacket of the present.

Although Wilde’s discursive foray into the world of art seems inappropriate, George Woodcock (1912-1995) notes in his excellent 1962 work Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements that

Wilde’s aim in “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” is to seek the society most favorable to the artist. (…) for Wilde art is the supreme end, containing within itself enlightenment and regeneration, to which all else in society must be subordinated. (…) Wilde represents the anarchist as aesthete.

Wilde, returning to the matter at hand, then decides to explore the realities of oppression:

There are three kinds of despots. There is the despot who tyrannises over the body. There is the despot who tyrannises over the soul. There is the despot who tyrannises over the soul and body alike. The first is called the Prince. The second is called the Pope. The third is called the People.

Wilde had clearly acquainted himself with the work of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527), who lived at a time when Italian princes and popes were constantly struggling for power. Indeed, Wilde accepts that either side can be cultivated, but each retains the wickedness and cruelty that finally explodes in despotism. This is a fact of history, of course, and we needn’t go into detail here, but Wilde’s inclusion of a third category – ‘the People’ – brings us back to his dismissal of democracy:

Their authority is a thing blind, deaf, hideous, grotesque, tragic, amusing, serious, and obscene. It is impossible for the artist to live with the People. All despots bribe. The people bribe and brutalise. Who told them to exercise authority? They were made to live, to listen, and to love. Someone has done them a great wrong. They have marred themselves by imitation of their inferiors. They have taken the sceptre of the Prince. How should they use it? They have taken the triple tiara of the Pope. How should they carry its burden? They are as a clown whose heart is broken. They are as a priest whose soul is not yet born. Let all who love Beauty pity them. Though they themselves love not Beauty, yet let them pity themselves. Who taught them the trick of tyranny?

Still reeling from his own frenetic detour into the world of art, Wilde cannot resist adding a few remarks about the absence of beauty under mob rule. Even so, he is correct to ascribe ‘the People’ with a category of their own although he never tells us how a Socialist agitator may avoid leading an army of potential despots in this direction. Perhaps it all comes down to the battle between the selfish and the selfless?:

Selfishness is not living as one wishes to live, it is asking others to live as one wishes to live. And unselfishness is letting other people’s lives alone, not interfering with them. Selfishness always aims at creating around it an absolute uniformity of type. Unselfishness recognises infinite variety of type as a delightful thing, accepts it, acquiesces in it, enjoys it. It is not selfish to think for oneself. A man who does not think for himself does not think at all. It is grossly selfish to require of ones neighbour that he should think in the same way, and hold the same opinions. Why should he? If he can think, he will probably think differently. If he cannot think, it is monstrous to require thought of any kind from him. A red rose is not selfish because it wants to be a red rose. It would be horribly selfish if it wanted all the other flowers in the garden to be both red and roses. Under Individualism people will be quite natural and absolutely unselfish, and will know the meanings of the words, and realise them in their free, beautiful lives.

For Individualism to succeed, Wilde says, egotism and competition must be replaced with a sympathy that both recognises suffering and celebrates the deeds of others. Not in the way that Christianity views pain as a necessary rite of passage in the quest for eternal joy, but with a view to overcoming it completely:

Nor will man miss it. For what man has sought for is, indeed, neither pain nor pleasure, but simply Life. Man has sought to live intensely, fully, perfectly. When he can do so without exercising restraint on others, or suffering it ever, and his activities are all pleasurable to him, he will be saner, healthier, more civilised, more himself. Pleasure is Nature’s test, her sign of approval. When man is happy, he is in harmony with himself and his environment. The new Individualism, for whose service Socialism, whether it wills it or not, is working, will be perfect harmony.

Finally, although in the twenty-first century The Soul of Man Under Socialism seems awfully utopian – and Wilde himself never shied away from the term – it continues to offer its readers a valuable insight into the stage that Anarchist philosophy had reached at the end of the nineteenth century. Enormous changes were afoot, things that Wilde could never have imagined, but the fundamental principles behind his evaluation of repressive authority and the role of property still hold true.