Book Review: Kratos by Jonathan Bowden

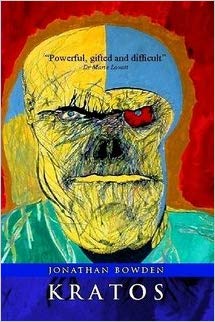

THE cover of this remarkable new publication from The Spinning Top Club is host to ‘Kratos I’, one of Bowden’s most gruesomely endearing paintings. Two mismatched eyes confront the reader with a sense of optical incompatibility, as a demonic bust with blackened snout, wide skull and brush-slashed features greets the world with a vacuous yellow smile. In total, there are four stories in this collection: ’Kratos’, ’Origami Bluebeard’, ’Grimaldi’s Leo’ and ’Napalm Blonde’. Throughout the book, and within each of the chapters, the text is broken up into a persistent litany of convenient extracts that resemble the little aphorisms that one might find in the work of Friedrich Nietzsche. Bowden, whom I know to be favourably predisposed to the writings of the famous German philosopher, will no doubt savour the comparison. The sections themselves also come with a series of bizarre one-liners, often rather amusing, which may or may not relate to the short paragraph which follows. But is this a random stream of consciousness or a calculated grammatical onslaught? You‘ll certainly have fun weighing up the possibilities, I know I did.

The first tale in this quartet, ‘Kratos’, contains three characters, all of whom are said to ‘battle in an ascendancy or non-gulf‘: Basildon Lancaster, Fervent Dominique and Odd Billy-o. Incidentally, perhaps I should mention at this point that the real Kratos is a figure from Greek mythology who is born with a slave-like mentality and throughout his life willingly obeys whatever Zeus instructs him to do. This led to Kratos developing no independent belief-system of his own and he became a creature without friendship or pity. The present adventure, on the other hand, begins with a dream-like figure walking through the thick, London fog. It is Lancaster, a man who narrates his story with a cacophonic blend of strange anecdotes, ethereal fantasy, twisted surrealism, wild conjecture, philosophical musing, blatant speculation, a hefty sprinkling of adjectives and all mixed in with a generous dose of descriptive cynicism. After spending a night at a seedy hotel room, Lancaster lumbers back to his cottage and is confronted with the sound of his wife – Fervent Dominique – screaming. At this point the narrative sways from side to side like a drink-addled zombie trying to negotiate his way down a cobbled street or perhaps like one of those blurred and oscillating dream-sequences you find in a Hannah-Barbera cartoon. And a dream, or perhaps even a nightmare, is precisely the setting in which the reader finds himself. Lancaster suddenly gets caught up in a sexual fantasy and it seems to take an eternity for the story to pick up where it left off, the words entangling themselves in an orgy of masturbatory innuendo and literary name-tagging. Then, in another twist, the married couple arrive by car at what seems to be another cottage (this time for sale) and are there confronted by the ramshackle character of Odd Billy-o (AKA Dung Beetle). The author continues to add to the general air of textual disorientation and its effect on the reader by causing them to question precisely who is doing what and when. In this extract, for example, is Lancaster knocking at somebody else’s door or knocking at his own: “After what seemed to be an interminable delay, perchance, a shabby man came to the wooden door. I rapped on its rough surface with a knocker, at once graven to a lion’s tooth.’ [p. 12] Or perhaps Bowden is simply working backwards for a moment, the door having been answered before the summoning knock had even been delivered? This is lucid story-telling at its best. Lancaster conceals his distaste at Billy-o’s appearance and comes straight to the point: ’I dispensed with such vagaries and turned up business’ flame.’ [Ibid.] It transpires that Lancaster and Dominique are interested in buying the property and the author’s depiction of class-based mannerisms in uncomfortable situations is wonderful: ’I extended a gloved or manicured hand, only to withdraw it speedily from his mallet. Was it really an entreaty? I noticed its curvature into felt or matted hair.’ [p. 13] Note, too, the hilarious juxtaposition between Billy-o – a Northern caretaker said to have been ’aborted from a maternal cervix like Piltdown man’ [Ibid.] – and the way Lancaster enjoys his ’rare Kensington & Chelsea cigarette’ [p.14]. Somehow, amid all the clandestine snobbery, a deal is finally struck. Before long, however, Lancaster appears to be transported back to his London hotel room, although, in reality, he is confined to a psychiatric hospital for the criminally insane and was apparently referring to a past existence that he finds difficult to think about. The landscape flits from imaginary pillar to illusory post. At one point Lancaster is a masked killer back in the cottage, his wife the victim of a frenzied attack. But soon afterwards he is back in the asylum and his wife is alive and well. In and out of the psychopathic portals we go, dragged along the weaving avenues of a deranged memory like prepubescent meat on the way to a pederast’s abattoir. Lancaster’s self-questioning testament – the thoughts of a ‘moon-staring gibberer’ [p. 27] – gives Bowden an opportunity to elaborate upon guilt and sympathy, to make a broad allusion to the master-servant relationship as outlined by Nietzsche and to consider the ills and shortcomings of the mental health industry. Not least the sounds and sights which characterise the environs of your average nuthouse, let alone the idiosyncrasies and ultimately irredeemable qualities of the inmates themselves. And, like Erik Skjoldbjærg’s 1997 film, Insomnia (remade in America), sleep – against which Lancaster fights tooth and nail, despite the fact that a severe dearth of it leads to yet more delusion – is portrayed here as a dangerous enemy. Hunger performs a similar role in Knut Hamsun’s 1890 novel of the same name. We reach Page 28 and the author suddenly decides to return us to the little cottage, where Dominique is being attacked by the hideous form of Odd Billy-o. Meanwhile, Bowden makes no attempt to mince his words when it comes to the nature of the psychologically-impaired: ‘A maniacal stare beams from the caretaker’s visage – truly, criminals are born and not made: they are the products of license and genetics. Each profound buffoon – in consequence – represents a recrudescence of impure blood. You see, Lombroso was right: moral inferiority results from a physical defect and the low are bound to exhibit the swinishness of how they look. The malefactor, therefore, is bred by virtue of an absence of oxygen to the brain at crucial moments. Can’t you tell Criminal Man from the placement of his eyes together in the skull; or those brown stains beneath either orb? Insanity has to be physiological; but evil and human ugliness are deeply interlinked at every level.’ [Ibid.]Consequently, like a cunning theatrical device the wobbly Crossroadsesque backdrop is hurriedly changed once again and Billy-o is seen to receive ‘electric shocks in a sensory deprivation chamber.’ [p. 29] But then a struggle ensues back at the cottage, where Lancaster – trapped in some kind of bizarre out-of-body experience – is thrown across the room by the caretaker. This appears to be a subtle analogy that very cleverly denotes how Lancaster himself becomes incorporated within the actual form of Billy-o. But the distinctions are soon blurred by the fact that our narrator begins to experience the caretaker’s dreams … As if his own weren’t really enough! Billy-o tries to dodge a cascading steel blade and Dominique makes a second appearance within the sterile hospital walls and ’stands alone and barefoot on hygienic floors’. Even Billy-o returns to try and murder her, amid a frenetic and incessant ‘tapping‘ [p. 36]. But Lancaster’s disjointed imagination is running wild and he switches erratically between the vision of Dominique in an adjacent cell to the events now taking place back at the cottage, where, to his immense horror, he discovers his own corpse and begins intoning in a Northern accent not dissimilar to Billy-o. In reality, of course, Lancaster has turned into the revolting creature he so despised and has returned to murder his wife. A perfectly ironic ending to a visual odyssey.

The second tale in this volume is ’Origami Bluebeard’, a fifty-part offering set in a decrepit suburban house in which the furniture is moth-eaten and garish and even the potted plants are wilting in sympathy. Trevelyan Bostock – a toy boy for whom an initial attraction to older women is fast losing its gloss – and his wife, the appropriately-named Candice Leper, are having marital difficulties and the husband is shown trying ‘to avoid her toilet-plunger lips’ [p. 49] as Bowden compares the basic human ’desire for love [to] a pullulating jelly-fish’. [Ibid.] Bostock, then, resists her feminine wiles and has no intention of ‘mounting those steps to a spider’s webbing’ [p. 50] because to engage with his wife would surely verge upon necrophilia. But he does respond when she begs him not to leave her. There is eventually a knock at the door and we are introduced to Man-Cloth, a tatterdemalion cum rag-and-bone man who used to buy old clothes from Mrs. Bostock. Trevelyan then questions the sense behind purchasing the pile of ’mildewed parchment’ being offered to Man-Cloth by his wife, but the latter pacifies their visitor and tells him later on that nothing has been damaged apart from their ’sense of bourgeois respectability’ [p.62]. Bostock is left alone and goes up into the attic, but he hears a noise from below and emerges to discover that Candice has returned with ’a large bag of swag’. Man-Cloth arrives once again to examine the contents, before Trevelyan decides to try to unearth his wife’s hidden fortune and is subsequently discovered. At this point the conversation is brimming with intellectual allusions that make the dialogue between this incompatibly married couple seem deliberately sarcastic, insincere and surreal. The pair have decided to ’engage in dialectic’ [p. 70] and the Catch 22 exchange becomes a winless game of draughts. At least for Bostock. I like the suggestion that Candice is disappearing nightly to procure rag-dolls for her ragamuffin accomplice, but Trevelyan himself has his own daily routine as he continues to search for her hidden fortune. But when his wife mocks him for his fruitless quest, he tells her that he is digging her grave and ends up plunging a pick-axe into her spine whilst resembling ’a fervent Punch who was murdering Judy in darksome splendour.’ [p. 78] Then, right in the middle of this homicidal episode – described at some length – Bowden even includes a plug for his new film … now that takes some doing! Inevitably, the next morning Man-Cloth reappears for his collection of rags and Bostock tries to palm him off with a few old towels and eventually dismisses him completely with strict orders never to return. He does, however, and after discovering Candice Leper’s grave in the cellar Bostock fires several shots into his body from an old blunderbuss. But neither that nor his trusty axe can kill the tatterdemalion and the two end up locked in deadly combat on the floor. It transpires, however, that Man-Cloth’s body is made up of ’pellets or shavings of canvas, dye, used curtain, tarpaulin, rug, bear-skin, fillet, combustible resin, fox-glove, stole, dyed blue-skins and Persian carpets.’ [p. 86] So Man-Cloth, therefore, as his name suggests, is ’animate clothing’ [Ibid.] and in a flurry of gory imagery he kills Bostock with ease. The author describes his story as ‘anti-feminist’, but I don’t find an enormous amount of that to be evident in the text and the ancient Heiress, despite her violent demise, is often seen to give as good as she gets. But then ‘anti-feminism’, of course, need not imply that Bowden is anti-woman per se.

The third story in the book is ’Grimaldi’s Leo’ – described by the author as a ‘John Aspinall ’passion’’ [p. 88] – and it is set around a travelling circus. Joseph Grimaldi (1778-1837), of course, was the so-called ‘King of Clowns’ who is still fondly celebrated and remembered by a legion of red-nosed admirers today. Bowden’s tale revolves around the story of an escaped lion, who also happens to be called Leonine Half or King Leo. And the image of the empty cage relates to Bowden’s examination of animal liberation, or at least according to philosopher-activists such as Peter Singer, who have turned what began originally as a worthy cause – certainly in terms of preventing vivisection and deliberate mistreatment, although the utopian notion of animal ‘rights’ leaves a lot to be desired – into yet another form of liberal victimology that echoes talk of ‘racism‘, ‘fattism’, ’ageism’ and all the other nonsense. Again, Bowden’s characters use intellectual terminology in order to engage in conversation, a philosophical method which allows the author to get his message across more effectively. After all, that’s precisely what this book represents; Bowden’s own thoughts are put into the mouths and expressed through the actions of the characters themselves. Winged Rhea, a trapeze artist, becomes a ‘Second Mrs. Kong’ [p. 91] as she defends the ‘right’ of the lion to be left alone and unfettered. Meanwhile, a debate ensues between Clown Joey (or Scaramouch) and the Lion’s tamer, the curiously-named Agent Naxos (I wonder if he likes Classical music?). The latter is convinced that his Beast would never even consider tasting human flesh, whilst Winged Rhea’s mood turns to anger and she attacks the Clown for daring to reduce the Lion to something wholly governed by the natural penchant for raw meat that such creatures are often renowned for. The debate rages on, this time about the ’theoretical halitosis’ [p. 98] that is political-correctness. Joey Clown continues to warn of the dangers presented by the escaped Beast, sounding more and more like an Apollonian archetype outlining the innumerable evils of the Chthonic realm and the threat they pose to civilisation. The rant is cut short by Sol Rasputin, the ring-master, who seeks to assert his authority. But the Clown continues, highlighting the flaws in Singer’s reasoning: ’If sentience happens to be the key to Professor Singer’s route-master then animals and men will forever wander unequally. Mental self-consciousness betrays a resilience under fire … Singer then resultantly slips into speciesism or non-human prejudice, basically because he has no other choice.’ [p. 102] Winged Rhea, says the Clown, ’addresses that killer cat as if it were a free-born Englishman.’ [p. 103] The Beast, by this time, is firmly under lock and key. Sol Rasputin exerts his authority once again and Agent Naxos assures him that from now on the Lion will be confined to his cage. A week later, however, the big cat escapes again and as the Lion Tamer is about to shoot his furry exhibit he is prevented from doing so by the ‘perfumed sleeve’ [p. 108] of the Trapeze Artist. She, instead, instructs the Lion to return to its cage amid ‘a ganja-laced atmosphere’ [p. 112]. The Lion does as it is asked and the implication – at least in the opinion of Winged Rhea, who now swaggers before Agent Naxos with a drug-infused arrogance – is that a more gentle and compassionate approach is preferable to more forceful or coercive means. But she saves much of her vitriol for Peter Singer, who would – presumably ‘to avoid suffering’ [p. 117] – gladly see the demise of all non-sentient beings, including circus freaks of all shapes and sizes. A while later, Winged Rhea falls from the high-wire and is miraculously saved by the Lion, who, by this time, has escaped yet again and now finishes the tale as a great hero.

Unlike its predecessors, the book’s final story, ’Napalm Blonde’, billed as a tragedy of Greek proportions, offers no introductory dramatis personæ. The central figure in this narrative, Scaramouch Ruby (or Lupin) is having an affair with her husband’s manager, Abel Cummings. Ruby makes no attempt to conceal her predatory and seductive nature: ’All that concerns a femme fatale like me, Abel, are the muscles, tendons and appended glands of a He-man.’ [p. 123] The betrayed husband, the brutishly-named Runter Bog, discovers his wife’s infidelity and Cummings makes his excuses through one of Bowden’s intellectually exaggerated conversation pieces: ’Dear me, my man, you have aggressively grasped the wrong end of a damaging stick with main force. It looks bad admittedly, but none can really arrange for an auction to be enacted using their own souls. Rely on me, Strong-Man, not to sully your family’s escutcheon with salt-petre.’ [p. 129] Bog spits out a series of descriptively lurid threats, as Cummings takes his leave in a fit of wild terror that suddenly gets metamorphosed into a dream. But the jealous husband is perfectly adamant that ’Adultery will be punishable by death’ [p. 133] and ’Armageddon chunters through Runter’s veins’ [p. 134] as both colours and surroundings change constantly and our tale begins to writhe around like a snake caught in the nightmarish throes of a bad acid trip. By this time Ruby has taken hold of a bread-knife and the couple seem to be encased within some kind of labyrinthine chamber. Bog becomes the Minotaur of Greek tragedy, at least momentarily, and the perceived sanctuary of the hidden corridors resemble a Bosch landscape and are then penetrated by the ever-advancing Runter Bog. Ruby and Abel find yet more corridors in their ever-changing maze of underground tunnels and make an attempt to enter one final chamber. The room, however, is a cell in a mental asylum and whilst Ruby is seen to be ’trussed up’ [p. 145], Abel Cummings ’continued to tap away in a manner which proved to be beholden to a vegetoid moment.’ [p. 146] The repetitious tapping and references to mental illness appear in ‘Kratos’, too, so the psychopathic quartet has now brought us full circle. But not before the pair try desperately to leave this latest room with Bog still hot on their heels, although when he reaches out to catch them Ruby finally silences him with a plank of wood. But the scenery shifts around yet again and Ruby Scaramouch changes into a vampire before her lover’s very eyes: ’All I wish to do is suck your BLOOD – we children of the night and daughters of Lilith must swallow such ichor in order to live! Demise can only be celebrated as a capturing of existence, you see?’ [p. 155] The seconds tick away and Cummings is hopelessly trapped between Death portrayed in two forms: first, as Beauty (Ruby) and, second, as Beast (Bog). For some, this book will prove rather difficult and in order to reap the full benefits prospective readers will need to concentrate and keep their wits about them. Bowden’s work is undoubtedly on an even keel with various other examples of high intellectual culture upon which the New Right looks favourably – including that produced by figures such as Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, Gabriele D’Annunzio and even T.S. Eliot – and, despite the stiflingly unappreciative epoch in which we currently find ourselves, it is vitally important that it is both viewed and appreciated in that vein.