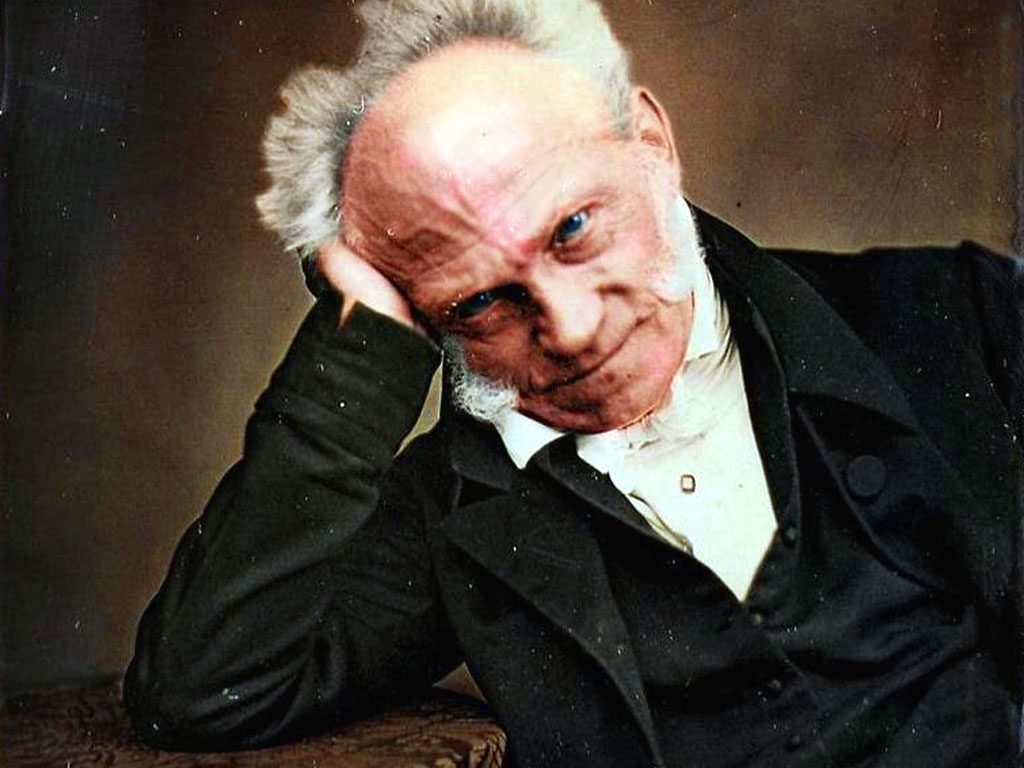

Schopenhauer and Suffering: Eternal Pessimist or Prophet for Our Times?

ARTHUR Schopenhauer was born in 1788 to a wealthy family living in the German city of Danzig, which has since been incorporated within Poland and renamed Gdansk. In 1809 Schopenhauer attended the University of Göttingen and studied Psychology and Metaphysics, before going on to devote himself to philosophers such as Plato and Kant (whom he later criticised). By 1813, at the tender age of twenty-five, he produced his On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason (1813) and then, one year later, began his Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung, or The World as Will and Representation, finally completing this important work in 1818. Two years later Schopenhauer became a lecturer at the University of Berlin alongside Friedrich Hegel and, despite the former’s attempts to engender a healthy competitiveness, was to eventually dismiss his more popular rival as ‘a clumsy charlatan’. This period marked Schopenhauer’s increasing disillusionment with the world of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century academia. Meanwhile, despite being portrayed as the quintessential doomsayer, in our modern world of accelerating meaninglessness Schopenhauer’s perceptive thoughts on suffering, morality, art and self-awareness need to be re-examined by a new generation of radical thinkers.

The main thrust behind Schopenhauer’s philosophical Weltanschauung is his forthright assertion that life is inextricably bound up with pain and struggle. In his own words:

all that opposes, frustrates and resists our will, that is to say all that is unpleasant and painful, impresses itself upon us instantly, directly and with great clarity.

In fact the German thinker’s main proposition is a close forerunner of Martin Heidegger’s interpretation of ‘the Nothing’; those rare, existentialist moments in which man is reminded of his own mortality. Evil, he argues, is preferable to good, because whilst the former is positive and makes itself palpable, the latter is negative and represents

the mere abolition of a desire and extinction of a pain.

In one of his most famous remarks, on the other hand, Schopenhauer contends that it is possible to demonstrate that enjoyment outweighs pain by comparing

the feelings of an animal engaged in eating another with those of an animal being eaten.

Indeed, it is hard to deny that life and death go hand in hand or that one only has to look around to witness great suffering and hardship among those who find themselves caught up in humanity’s endless and inevitable obsession with conflict and aggression. But Schopenhauer also believes that we are under threat from a different quarter, that of Time,

which never lets us so much as draw breath but pursues us all like a task-master with a whip. It ceases to persecute only him it has delivered over to boredom.

This issue was examined more recently by the Anarchist thinker, George Woodcock, in his highly relevant essay The Tyranny of the Clock (1944). But whilst Woodcock views Time as a form of social and economic control, Schopenhauer explains that Time is linked with suffering because it actually fills a void and thus helps to alleviate the monotony and tediousness of human existence.

Schopenhauer’s belief that contentment can be measured, not by the amount of happiness within people’s lives, but in terms of the absence of suffering that we often have to endure as part of our basic presence upon the earth, is something that developed as a result of his study of behaviour in the animal kingdom. But whilst the other creatures of the earth share our desire to provide food, shelter and warmth for ourselves and our loved ones, humans are infinitely more passionate when it comes to securing these simple necessities:

This arises first and foremost because with him everything is powerfully intensified by thinking about absent and future things, and this is in fact the origin of care, fear and hope, which, once they have been aroused, make a far stronger impression on men than do actual present pleasures or sufferings, to which the animal is limited.

Animals, of course, by living entirely in the moment, are completely unable to reflect upon their lives in the way that we humans do and therefore when things become either problematic or comparatively easier they do not suffer the corresponding feelings of despair and relief or possess the same aspirations for the future. Humans inevitably heighten these feelings by using drugs or alcohol, particularly today, and this results in people going beyond their basic needs and making themselves unhappy.

Boredom, too, according to Schopenhauer, is also an inescapable part of the human experience and this, too, is not felt by animals. There is a good reason for all this, of course, and man’s superior intellect means that he is able to dwell upon the nature of his own circumstances, be they good or bad. The tendency towards suffering occurs when man becomes aware of his impending death, whilst “the animal only instinctively flees it without actually knowing of it and therefore without ever really having it in view”. Schopenhauer believes, therefore, that animals and plants are far more content with their lives than humans, although in many cases it all depends “how dull and insensitive he is”.

Indeed, as we read in the words of the English poet, Thomas Gray, “Where ignorance is bliss, ’tis folly to be wise,” but if animals lack intellect, they also experience far less pleasure than we do because an absence of anxiety is overshadowed by a deficiency of hope and joy for the future. Another reason for Schopenhauer’s association between superior intellect and pain is due to the fact that the nervous system is connected to the brain. Pain, therefore, and the threat of suffering, will always end up frustrating or impeding the will. As life progresses, pain and suffering tend to increase and the end result is always physical death. This leads Schopenhauer to consider whether life itself serves any real purpose, not least as a result of the fact that so many religions posit the idea that earth is actually a form of hell in which mankind is forced to suffer on account of his sins. This leads Schopenhauer to reject the notion that there is some kind of divinely orchestrated scheme at the root of our existence, preferring, instead, to attribute the miseries of mankind to the metaphysical guilt incurred through the age-old belief in original sin:

For our existence resembles nothing so much as the consequence of a misdeed, punishment for a forbidden desire.

However, Schopenhauer also believes that Old Testament allusions to a Fall of Man serve a far greater purpose than an endless and potentially futile pursuit of heaven, because they prepare us for the suffering and hardship that we are bound to encounter throughout the whole of our lives. This need not cause us to embrace those religions which promote such doctrines, but adopting the general ethos of this concept will ultimately help to shatter the dangerous illusions held by the modern progressives with their utopian, pseudo-egalitarian fantasies about ending war and poverty.

Schopenhauer was not a pessimist, he was a realist, and we can do a lot worse than seek to acknowledge the stark realities of the human condition and prepare ourselves for the trials and tribulations of the future.